Rowzie Remembers Running the Cannonball

By Katherine Cobb

Published by The Observer in January 2008

Published by The Observer in January 2008

In 1971, a group of rebellious drivers participated in the first “Cannonball Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash,” popularly known as the “Cannonball.” The outlaw road race challenged its participants to drive from New York to Los Angeles as quickly as possible and quicker than everyone else.

Named after the great transcontinental driver Erwin G. “Cannon Ball” Baker, known as the greatest cross-country record-breaker of them all, the Cannonball ultimately became one of the most legendary road races in history.

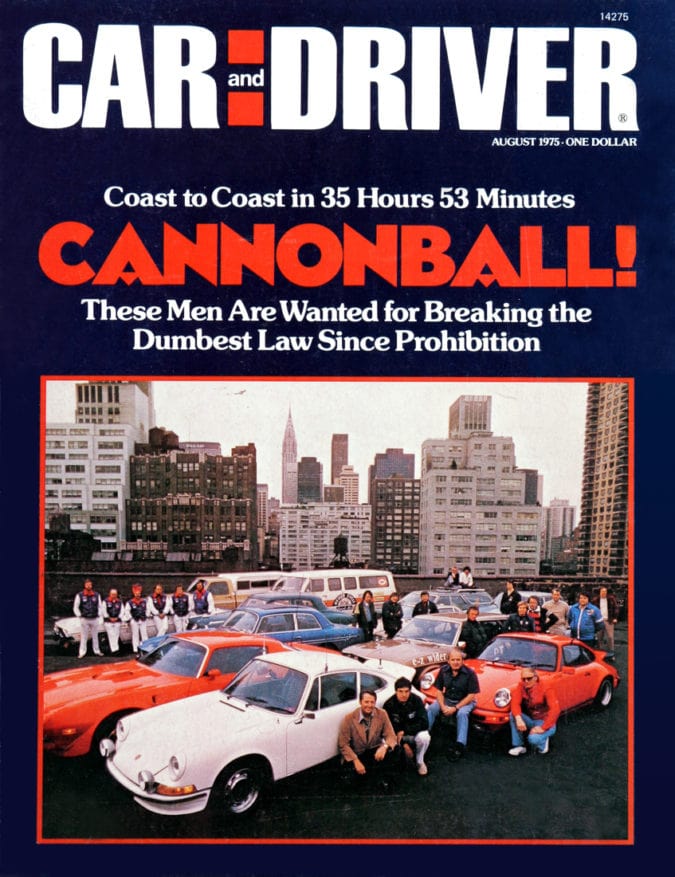

Charles Town resident and car enthusiast Dan Rowzie went along for the ride in the fourth Cannonball in 1975. He and co-driver Leo Lynch earned a respectable fifth place after driving 38 hours and 39 minutes in their 1973 Porsche 911RSR. The winners’ time was 35:53 with a total of 18 cars in the competition that year.

To this day, Rowzie and Lynch hold the record for having the top finish for a 911 in all of the Cannonballs.

There were only five Cannonball Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dashes to ever be run. The first contest drew interest from the likes of actor Robert Redford, former Sports Illustrator writer Kim Chapin and humorist Jean Shepherd. Many others expressed interest, even agreed to participate, but ultimately, everyone dropped out for various reasons, leaving only one car containing Car and Driver writer Brock Yates (dubbed “father” of the Cannonball), artist and writer Jim Williams, mechanic and club racer Chuck Kreuger and Brock’s 14-year-old son, Brock Jr. The four of them drove a 1971 Dodge Custom Sportsman van the length of the trip, leaving at midnight on May 3, 1971. Because it was really just four guys in a van seeing how fast they could make the journey, they didn’t really count it as the first Cannonball, even though it was, technically. Subsequent races had as few as eight and as many as 46 competitors with some vehicles unable to finish the race. Entrants weathered plenty of hazards and challenges along the way from car problems to poor weather conditions to getting “finked on” by truckers to law enforcement.

All participants were required to pay the $50 entry fee plus donate $200 to their favorite charity. According to Yates, they then selected the final teams based on “arbitrary judgements involving driving credentials, type of car, personality stability and general karma.” While participants may have differed, one theme stayed strong throughout all the Cannonballs: There’s only one rule: there are no rules.

What was the motivation for the Cannonball, some might ask? Yates wrote the Cannonball was run for two distinct reasons—one frivolous, the other quite serious. He viewed it as “an adventure for people who really care about cars and drivers in the real-world environment (as opposed to the laboratory environs of the racetrack).” The weightier purpose of the Cannonball was to “prove the validity of high-speed Interstate travel (as opposed to the oppressive lunacy of the 55 mph speed limit) both in terms of safety and economic efficiency.”

Some people may only have learned about the Cannonball through the Hollywood rendition that was released years ago, but apart from actors leaving from New York and arriving in Los Angeles, there wasn’t much about the movie that resembled the real race.

Rowzie, on the other hand, remembers the real thing like it was yesterday.

How did you initially hear about the Cannonball?

I guess I read about it in Car and Driver magazine. It was the kind of idea that sparked everyone’s imagination...at least for all the car guys. It was the kind of thing that people had talked about doing for a long time. It’s a competitive thing...whenever there’s a chance to set a record or go from point to point in a certain time, it sparks interest. And Erwin Cannon Ball Baker, who the race is named after, did 143 cross country record attempts with cars and motorcycles. His most incredible feat was driving a Graham-Paige Model 57 Blue Streak 8 across the nation in 53-1/2 hours back in the 30s. If you think about that, he was driving on a lot of dirt and gravel roads, in a car that didn’t go very fast, with a half-hour of sleep, all singlehandedly. It was fitting that the race be named after Baker...and when I read about how Brock Yates from Car and Driver got in the van with his son and set the stage for it, I was interested. Then world famous race car driver Dan Gurney and Yates got some people together the following year and that was the real start of the thing. When Gurney and Yates teamed up in their Ferrari Daytona and set the record at 35:54, it became the benchmark that we all shot for in the ensuing Cannonballs.

What made you decide to run it?

I found out that Leo Lynch, a friend of mine from Pennsylvania, had done the 1972 Cannonball in his Porsche. He had an engine failure so never finished. I told him if he ever wanted to do it again, I would gladly be his co-driver. In April of 1975, I got a call. It was almost like the movie, “Gumball Rally,” when the guy calls up and just says, “Gumball Rally” into the phone. I was sitting at my desk, and he said, “You want to go on the Cannonball?” and I said “Yeah!” When I hung up, I wasn’t sure if it was such a good idea after all, wondering if something would happen, if I would lose my security clearance at my job. You don’t know if you’re going to be put in jail or what might happen. I even went to AAA to get the bail bond they offer, that came with my membership—just in case I needed it.

How old were you at the time and what were you doing professionally?

I was 38, single and working for the Department of Navy’s Trident Missile Program as an analyst.

What went well during the 38 hours and 39 minutes you were on the road?

The car ran faultlessly. The car was very fast. We had no incidents, no wrecks, no close calls. We weren’t driving recklessly.

What’s the fastest you went?

Pretty fast in different places. If conditions allowed, we went very fast, like 120 or 130. We were trying to get that record and we had calculated we would have to go 80 mph every minute of the trip, even when we were getting gas. So sometimes, you had to be well in the hundreds to maintain that average, to make up for the down time. We were able to average only about 75 mph.

What went wrong?

At the time this was done, it was the beginning of the 55 mph speed limit, and it was zealously enforced. The radar detectors were very crude and not as sensitive as they are now, so we missed the first police car—didn’t even hear him and he turned around and picked us off. Another thing that didn’t work in our favor was having to take a southern route. We didn’t have a heating system in our car, and it was cold, so we drove where it was warmer, but then got several tickets on I-81 in Virginia. We had an unplanned, unscheduled stop at Howard Johnson’s in New Jersey to ensure the police didn’t catch us. We had heard on the CB radio that they were looking for us so we pulled in for coffee and could see the police going back and forth looking for us. It seemed like a hundred police cars going by with the lights and everything. Finally, they left, but we knew they had gone down to the toll gate entrance right up the road and were waiting for us up there. We were able to slip out and elude them. Then we got the tickets in Virginia. We had gotten word that police were in the vicinity, so we went slowly but after a while, when nothing happened, we sped up again and one nailed us. That policeman was actually a nice guy and knocked the speed down a little, which in turn, kept the ticket price down. Some of our tickets were expensive. Then we got another ticket in north Little Rock, in Arkansas, on my first drive. The only other downfall was that I couldn’t sleep when I needed to; I was too excited.

Some people say the police were tipped off when the Cannonball was running. Was this true?

Oh yeah, the truckers were wild. They couldn’t tell on you fast enough back then because it took the heat off them. Leo and I were not able to communicate with our CBs, only listen. This was a deficit, but we didn’t have enough time to install it properly before we left.

Did you get anything for participating?

There were no trophies, no prizes. We got nothing other than the privilege of paying our money to enter and running the race. I think in the final race, they had a wreath for the winner.

If you could do it again today, would you?

Probably.

Why do you think the Cannonball was so popular?

It ignited a spark in car enthusiasts. What I said earlier about the possibility of setting records, there was just the romance of doing it and doing it well. Also, there was a lot of talk and anger about the high-speed interstate system and the government enacting the 55 mph speed limit. It didn’t used to be that way and it created an anti-establishment attitude, a rebellion of sorts. That’s part of what the Cannonball grew out of. Ultimately, the 55 mph speed limit was ineffective and not the energy saver it was supposed to be—that’s why it has been raised in most places. The other thing was we all had high-speed training. It’s not like we were going out there to be reckless. Brock Yates looked at your experience before you could drive in the Cannonball.

So why did it stop running?

I don’t know. I think it was pressure...corporate pressure. Car and Driver merged with some other magazines. It got bigger and became a conglomerate. It was bought up by another, larger publisher and there was pressure to not do it or have it associated with Car and Driver. Then Yates sold the rights, and the movie came out.

What did you think of the movie “Cannonball Run” when it came out?

It was ridiculous. Stupid. Yates sold out and then later apologized. He got a bunch of money for selling the rights, but he felt badly later because of what they did with it — a typical Hollywood mess. “Gumball Rally” is actually a pretty good representation of Cannonball, a lot better than the other movie.

You have a history with cars beyond the Cannonball. Can you tell me a little about that?

I’ve liked cars since I was a young teenager when I used to fix up and customize cars. Then I got into hot rods and then moved into sports cars. I became enthralled with race cars and bought a 1948 MG TC and then I developed a love for the Porsche but was unable to buy one until 1965. I have had one ever since...a lot of them in fact. Some of them have been pretty exotic and collectable. A lot of them weren’t worth much then but now they are. I’ve had a few hot rods and other cars and lots of motorcycles. I’ve been involved in several car clubs over the years. I was a national officer in Porsche Club — I’ve had a bunch of national posts. I was also president of the local Washington, D.C., Porsche Club. I’ve also done a lot of high-speed professional driver schools and solo racing.