WORLD CHAMPIONS OF THE PANHANDLE

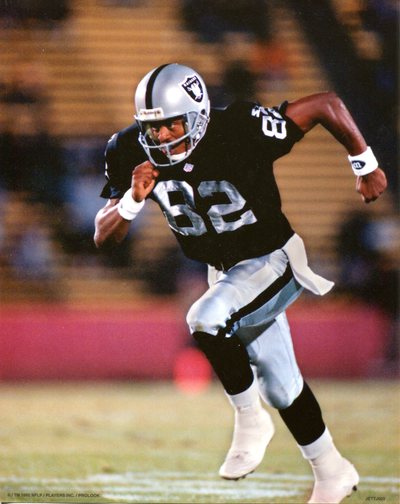

Jett-Propelled: James Jett the Fastest Man to Ever Run Track in West Virginia

There is no better last name for James Jett, who is considered the fastest man to ever run track in West Virginia in any era, and who still holds state track records nearly three decades after graduating from high school. Not to mention, that long professional football career at which he also excelled.

A Charles Town native, Jett attended Jefferson High, ending his high school career with seven state track titles (five individual), four state records, two high point titles and several personal records. In football, he played quarterback and wide receiver and earned an all-state selection his senior year. He attended West Virginia University on a football scholarship and became a four-year starter. He also ran track, where he was named All-American seven times and held five WVU records. In 1992, his junior year, he came in second place in the 100- and 200-meter finals at the NCAA championships and earned a spot on the men’s U.S. Olympic 4 x 100 meter relay team after placing fifth in the 100-meter trials. At the Olympics, Jett ran as the anchor in the preliminary race to help the team secure its place in the final. The team won gold for their time of 37.40, a world record.

After graduation, Jett signed with the Los Angeles Raiders as an undrafted free agent following the 1993 NFL Draft and played nine seasons as a professional football player, including an appearance in Super Bowl XXXVII. He won the NFL Fastest Man Competition in 1996 (and placed second the following year) and finished his career as the eighth-leading receiver in Oakland Raiders team history. His career totals include 256 catches, 4,417 yards and 30 touchdowns. He led the AFC with 12 touchdowns in 1997. In 2002, he was inducted into the WVU Sports Hall of Fame. He is listed as one of the six best NFL players who were Olympians.

Jett currently lives in Martinsburg, and no matter where his travels have taken him, has always come home to the panhandle.

You had an impressive career in both track and football. How did you get involved in the sports?

In junior high, I played football two years. I noticed I could run fast. Then I played football at Jefferson and the track coach noticed me and asked me to come out, Coach Jim Taylor. I got beat my first year. But then the next year, I won the 100, 200 and two relays. I told the coach I could win three individual titles and then said, ‘You know what would be even crazier? To break records for all three.’ He used that reverse psychology on me and blew me off. But a few weeks prior, we had to qualify and I was still talking about the triple. I was out there busting my heart out and it was brutal, but it paid off in the end. I ended up going to states and winning the 100, 200 and 400. I did the first two and broke the records. I had never run the 400 but I told the coach I was going to give it a try. I had a strategy, but it was the weirdest feeling, when I hit the last straightaway, everyone was standing up and clapping and I didn’t know why just then. But I ended up getting the state record. It’s still a record to this day.

At Jefferson, you continued competing in track and football. It seems you were destined to do both sports. Did you prefer one or did you feel they complimented each other?

I think they complimented each other. I didn’t get burnt out. Football came first, I’d have a rest then track would come. Track helped with the football because of the speed. Strength helps with the running. The good came with the bad.

You received a scholarship to WVU for football. Were you thinking you’d only play football at that juncture or did you plan to pursue track as well?

Prior to going there, I asked if I could run track as well. My goal was to see how far I could go with both.

You accomplished a lot in your four years at WVU in both football and track. You were a four-year starter at wide receiver and the only freshman to play on WVU’s 1989 Gator Bowl team. What did that feel like to reach a bowl game in your first season as a Mountaineer?

I was young and dumb. I didn’t know anything. Actually, I was fortunate to even be there and play in the game. It was a great experience to go to the bowl. We scored the first touchdown of the game — and I scored it — but then it got pretty ugly after that. So that was the highlight. And we got to go to a different state. That was the most I’d traveled other than within the state of West Virginia.

At the end of your college career, your football stats placed you at eighth among Mountaineer career leaders, and in track, you were a seven-time All-American. What do you attribute your obvious success to?

People always talk about speed. You’ve got to be born with it and then hone your skills, make the best with what you’ve got. My coaches pushed me and I wanted to prove I could go that much farther. I wanted to make my family proud of what I’d done. Back in even high school, I would run to the store and get the paper and see what they wrote about me and I’d cut out the articles.

You were a junior in college and headed down to New Orleans for the U.S. Olympic Trials. Did you think you had a pretty good shot?

It was actually really weird. In 1990, I was young. I remember going to New York and running in the championships and these guys were like, blazing, and I couldn’t even get out of the blocks. But in the next two years, I didn’t realize how much of a change there had been. When I got there, I was running good, peaking at the right time.

What happened at the trials?

I ran the preliminary rounds and got to the finals…there were eight or nine of us. I was feeling good. All of a sudden, we’re in the blocks and I’m ready to go, and bang bang, a false start. I ran out then turned around. When I came back, I was a nervous wreck. I lost my composure and the focus was just gone. It was the worst I’d run, but I still ended up fifth, which was enough to qualify.

Then you headed to Barcelona after securing your spot on the 4x100 Olympic relay team. Tell me about that experience.

I was happy to be there at all in Barcelona. I was an alternate. There were six guys on the team, and two of us were alternates. I ran the fourth leg in the preliminary and ran well. Our team earned its place in the final. But it got real political, real fast. I could see it coming. What happens, if somebody gets hurt, is you’re the one to come in as the alternate. I was the fifth guy in the lineup, which meant I would have been the first one in if that happened.

And it did happen, when your teammate, Mark Witherspoon, collapsed the night before the semifinals with a ruptured Achilles’ tendon in his 100-meter event.

Yes, I was watching that race back in the Olympic Village and when Mark went down, someone said that meant I would be the one to run the final relay race. To even think that was a possibility was like a dream, but it didn’t happen that way. They set it up to bring Carl Lewis in — he had the name and I didn’t. So it seemed to be all about that. Carl ran the final leg and we won a gold medal.

You outran Carl Lewis in the 100 meters during prelims. That had to feel pretty good. How many times did you compete with Lewis?

Then and back in 1990, up in New York, back when he and a few other guys were in a different league. Yeah, it felt good! At the trials, we were on the infield warming up and this guy came up and asked me what was up and it was Michael Johnson. He said, ‘You know a little something about track, eh?’ That was something.

Winning an Olympic gold medal must have been a powerful moment.

It was unbelievable.

After graduating from WVU, were you feeling confident you’d get drafted into the NFL or was it your goal to return to the Olympics?

You grow up to play football. You don’t grow up to run. Everybody loves football. I loved running and catching, and so after I got there, I didn’t realize how big track could be. Back then, you had to be elite in track to get paid. But football was my first love and I wanted to go as far as I could in the sport. I figured if that didn’t work out, I’d fall back on track.

Despite your ability, you weren’t drafted because you were seen as a track star. Luckily, Raiders owner Al Davis thought differently and you signed as an undrafted free agent in 1993. How did all that materialize?

You do get labeled a track guy, and that makes it harder. It’s all how you get labeled. I had an agent though he called after the draft ended and told me Al called. I went out to California, signed and the rest is history.

I was born and raised in Oakland, California so I’ve always been a Raiders fan. When you first signed, the team was in Los Angeles, before moved back to Oakland. Both cities are a big departure from our small town life over here in the West Virginia. What about it was good and bad?

Going from West Virginia to LA was a culture shock. It was crazy. There was always something going on and I don’t know how I did it, but I stayed out of trouble. It probably helped me to be from a place like this. It’s like a wide-open freeway and you just get on it. Going from college where I was broke and it was rough to getting big checks and the phone ringing off the hook was like zero to 60. More money, more problems. You get caught up in the lifestyle. Guys are chirping and talking all the time, telling you to buy the expensive car or whatever. It’s a whole lot of testosterone. And you want to be with the in crowd. I can recall my first year playing in LA, I didn’t think I was gonna play at all so I was just happy to be there. All of a sudden they throw me out there. I was on the field in one of those early games and I was standing in the huddle and they called a time out. I stood there and I looked over and saw the big emblem on the side of one of my teammate’s helmets and I got chills. It hit me I was playing for the Raiders! It was like a dream, again. First I’m in the Olympics. Now I’m playing for the Raiders.

I know there’s a learning curve between college and pro football. You played 13 of 16 games your rookie season and seemed to do well. Who or what helped you make that transition so well?

I got lucky, getting to be in the right place at the right time. A lot of people don’t get the opportunity. They have the talent, but don’t get to chance to get in the games. In the preseason, I was scared. The ball beat me up pretty good. Like that Hall of Fame game in Ohio. That was bad, a mess.

You played in every game your first three seasons, but not as a starter until your fourth season when you also won the NFL Fastest Man Competition. Who did you beat to get it?

That was great. We thought it was going to be a Raiders-only race, but there were about 12 guys there from all the teams. The players picked were known for speed but it was one of those things where it was up to you if you wanted to participate. Me and Trapp [James Trapp, another track star] came from the Raiders. We ran a prelim then got down to the final three. I was fortunate to beat my teammate and win it.

In 1997, you ranked second among NFL receivers with a personal-best 12 touchdowns and a career-high 46 receptions for 804 yards. You’d reach another career high the following season. You must have been on top of the world.

It was all about timing, opportunity and having the right people in the right places. We had a good offense but no defense. We put record numbers on the board for offense. Quarterback Jeff George had a gun. He loved to throw that ball downtown. He used to tell me to ‘get ready cause it’s coming.’ The game that started it all was Atlanta. He gave me a signal and I caught it with one hand and ran it for a touchdown and that was the beginning of me leading the league in scoring.

The Raiders had some lean years but you played for the organization when they won some wild card and divisional playoffs, and in 2002, made it all the way to the Super Bowl, which was lost to Tampa Bay. What were the highlights?

My first year was probably one of the most memorable. I was a Bronco fan, so it was weird when we went to Mile High Stadium. My number got called and I ran the ball back for a 74-yard touchdown and it was wild. The first year we went to the playoffs was huge, too. Of course we played Denver again. We played them twice…the last game of the season and then the wild card game. I ended up scoring in the wild card game. But I was tired and washed out. It was my first year and the pro football schedule is rough. We ended up winning and going to Buffalo for the divisional playoff game. We got up there and it was cold. It’s not easy after living in California. All year, we’ve lived and died by the pass but we get there, and they can’t stop the run so we ran the ball. That strategy worked the first half, but I was wondering why were still doing it in the second. And we lost. We should have won that game.

You finished your career as the eighth-leading receiver in Oakland Raiders history, an impressive legacy. Did you leave the sport feeling satisfied?

Everybody wants to play and thinks they’re invincible. There is always someone coming in and trying to take your place that is younger, faster and stronger. I knew if I got so many years, I would be happy. The average NFL career is three-and-a-half years, and I got to play a lot longer than that. I can’t complain.

What football players and track stars meant the most to you during your career and do you keep in touch with any of them now?

When Jerry Rice came over from the 49ers, we were like boys, getting in trouble. We became good friends. I talk to him and Tim Brown. Harvey Williams, who was a running back, and I play golf together. A few years back, when Al died, his son had a big thing for him in Vegas. That’s where Al went every year on his birthday. His son brought in everyone who meant something to Al. It was great to get together with the guys. Once you finish playing, everyone moves on and you don’t really keep in touch so it was great to go back and bump into a lot of guys and just see them and touch elbows again. It makes you want to keep in touch. You never know when you’re going to hit the bottom of the barrel or get a condition.

How did you transition to a life after track and pro football?

It’s been rocky, like anything else. I’m married now with three kids. It’s been a big transition, as far as stopping working. Things change but you still have priorities. I was fortunate to play as long as I did, so I have some things lined up that a lot of guys don’t have. Or guys get banged up and can’t remember things.

One last thing — how fast do you think you could run the 100 now?

I was pretty good at getting up before, but once I stopped working, now I don’t want to get out of bed. I go down to the gym and try and stay halfway healthy, but run the 100? Maybe in 20. It won’t be no 10! I’d probably pull a hamstring.

JAMES JETT AT A GLANCE

Sport: Track and professional football

World championship titles: Olympic gold medalist in 1992 but also known for being the fastest man in West Virginia in any era, and as one of the six best NFL players who were Olympians

Personal bests: 10.10 seconds in the 100 meters, 19.91 seconds in the 200 meters; finished football career as the eighth-leading receiver in Oakland Raiders history

Nickname: On the Raiders, known as “Batman”

Years active (in any sport post high school): 14

Hometown: Charles Town

Current residence: Martinsburg

Age: 45

Family: Married to Amy. Three children: son James Jr., 18 and daughter Jordan, 18 (twins) and daughter Ava, 5

A Charles Town native, Jett attended Jefferson High, ending his high school career with seven state track titles (five individual), four state records, two high point titles and several personal records. In football, he played quarterback and wide receiver and earned an all-state selection his senior year. He attended West Virginia University on a football scholarship and became a four-year starter. He also ran track, where he was named All-American seven times and held five WVU records. In 1992, his junior year, he came in second place in the 100- and 200-meter finals at the NCAA championships and earned a spot on the men’s U.S. Olympic 4 x 100 meter relay team after placing fifth in the 100-meter trials. At the Olympics, Jett ran as the anchor in the preliminary race to help the team secure its place in the final. The team won gold for their time of 37.40, a world record.

After graduation, Jett signed with the Los Angeles Raiders as an undrafted free agent following the 1993 NFL Draft and played nine seasons as a professional football player, including an appearance in Super Bowl XXXVII. He won the NFL Fastest Man Competition in 1996 (and placed second the following year) and finished his career as the eighth-leading receiver in Oakland Raiders team history. His career totals include 256 catches, 4,417 yards and 30 touchdowns. He led the AFC with 12 touchdowns in 1997. In 2002, he was inducted into the WVU Sports Hall of Fame. He is listed as one of the six best NFL players who were Olympians.

Jett currently lives in Martinsburg, and no matter where his travels have taken him, has always come home to the panhandle.

You had an impressive career in both track and football. How did you get involved in the sports?

In junior high, I played football two years. I noticed I could run fast. Then I played football at Jefferson and the track coach noticed me and asked me to come out, Coach Jim Taylor. I got beat my first year. But then the next year, I won the 100, 200 and two relays. I told the coach I could win three individual titles and then said, ‘You know what would be even crazier? To break records for all three.’ He used that reverse psychology on me and blew me off. But a few weeks prior, we had to qualify and I was still talking about the triple. I was out there busting my heart out and it was brutal, but it paid off in the end. I ended up going to states and winning the 100, 200 and 400. I did the first two and broke the records. I had never run the 400 but I told the coach I was going to give it a try. I had a strategy, but it was the weirdest feeling, when I hit the last straightaway, everyone was standing up and clapping and I didn’t know why just then. But I ended up getting the state record. It’s still a record to this day.

At Jefferson, you continued competing in track and football. It seems you were destined to do both sports. Did you prefer one or did you feel they complimented each other?

I think they complimented each other. I didn’t get burnt out. Football came first, I’d have a rest then track would come. Track helped with the football because of the speed. Strength helps with the running. The good came with the bad.

You received a scholarship to WVU for football. Were you thinking you’d only play football at that juncture or did you plan to pursue track as well?

Prior to going there, I asked if I could run track as well. My goal was to see how far I could go with both.

You accomplished a lot in your four years at WVU in both football and track. You were a four-year starter at wide receiver and the only freshman to play on WVU’s 1989 Gator Bowl team. What did that feel like to reach a bowl game in your first season as a Mountaineer?

I was young and dumb. I didn’t know anything. Actually, I was fortunate to even be there and play in the game. It was a great experience to go to the bowl. We scored the first touchdown of the game — and I scored it — but then it got pretty ugly after that. So that was the highlight. And we got to go to a different state. That was the most I’d traveled other than within the state of West Virginia.

At the end of your college career, your football stats placed you at eighth among Mountaineer career leaders, and in track, you were a seven-time All-American. What do you attribute your obvious success to?

People always talk about speed. You’ve got to be born with it and then hone your skills, make the best with what you’ve got. My coaches pushed me and I wanted to prove I could go that much farther. I wanted to make my family proud of what I’d done. Back in even high school, I would run to the store and get the paper and see what they wrote about me and I’d cut out the articles.

You were a junior in college and headed down to New Orleans for the U.S. Olympic Trials. Did you think you had a pretty good shot?

It was actually really weird. In 1990, I was young. I remember going to New York and running in the championships and these guys were like, blazing, and I couldn’t even get out of the blocks. But in the next two years, I didn’t realize how much of a change there had been. When I got there, I was running good, peaking at the right time.

What happened at the trials?

I ran the preliminary rounds and got to the finals…there were eight or nine of us. I was feeling good. All of a sudden, we’re in the blocks and I’m ready to go, and bang bang, a false start. I ran out then turned around. When I came back, I was a nervous wreck. I lost my composure and the focus was just gone. It was the worst I’d run, but I still ended up fifth, which was enough to qualify.

Then you headed to Barcelona after securing your spot on the 4x100 Olympic relay team. Tell me about that experience.

I was happy to be there at all in Barcelona. I was an alternate. There were six guys on the team, and two of us were alternates. I ran the fourth leg in the preliminary and ran well. Our team earned its place in the final. But it got real political, real fast. I could see it coming. What happens, if somebody gets hurt, is you’re the one to come in as the alternate. I was the fifth guy in the lineup, which meant I would have been the first one in if that happened.

And it did happen, when your teammate, Mark Witherspoon, collapsed the night before the semifinals with a ruptured Achilles’ tendon in his 100-meter event.

Yes, I was watching that race back in the Olympic Village and when Mark went down, someone said that meant I would be the one to run the final relay race. To even think that was a possibility was like a dream, but it didn’t happen that way. They set it up to bring Carl Lewis in — he had the name and I didn’t. So it seemed to be all about that. Carl ran the final leg and we won a gold medal.

You outran Carl Lewis in the 100 meters during prelims. That had to feel pretty good. How many times did you compete with Lewis?

Then and back in 1990, up in New York, back when he and a few other guys were in a different league. Yeah, it felt good! At the trials, we were on the infield warming up and this guy came up and asked me what was up and it was Michael Johnson. He said, ‘You know a little something about track, eh?’ That was something.

Winning an Olympic gold medal must have been a powerful moment.

It was unbelievable.

After graduating from WVU, were you feeling confident you’d get drafted into the NFL or was it your goal to return to the Olympics?

You grow up to play football. You don’t grow up to run. Everybody loves football. I loved running and catching, and so after I got there, I didn’t realize how big track could be. Back then, you had to be elite in track to get paid. But football was my first love and I wanted to go as far as I could in the sport. I figured if that didn’t work out, I’d fall back on track.

Despite your ability, you weren’t drafted because you were seen as a track star. Luckily, Raiders owner Al Davis thought differently and you signed as an undrafted free agent in 1993. How did all that materialize?

You do get labeled a track guy, and that makes it harder. It’s all how you get labeled. I had an agent though he called after the draft ended and told me Al called. I went out to California, signed and the rest is history.

I was born and raised in Oakland, California so I’ve always been a Raiders fan. When you first signed, the team was in Los Angeles, before moved back to Oakland. Both cities are a big departure from our small town life over here in the West Virginia. What about it was good and bad?

Going from West Virginia to LA was a culture shock. It was crazy. There was always something going on and I don’t know how I did it, but I stayed out of trouble. It probably helped me to be from a place like this. It’s like a wide-open freeway and you just get on it. Going from college where I was broke and it was rough to getting big checks and the phone ringing off the hook was like zero to 60. More money, more problems. You get caught up in the lifestyle. Guys are chirping and talking all the time, telling you to buy the expensive car or whatever. It’s a whole lot of testosterone. And you want to be with the in crowd. I can recall my first year playing in LA, I didn’t think I was gonna play at all so I was just happy to be there. All of a sudden they throw me out there. I was on the field in one of those early games and I was standing in the huddle and they called a time out. I stood there and I looked over and saw the big emblem on the side of one of my teammate’s helmets and I got chills. It hit me I was playing for the Raiders! It was like a dream, again. First I’m in the Olympics. Now I’m playing for the Raiders.

I know there’s a learning curve between college and pro football. You played 13 of 16 games your rookie season and seemed to do well. Who or what helped you make that transition so well?

I got lucky, getting to be in the right place at the right time. A lot of people don’t get the opportunity. They have the talent, but don’t get to chance to get in the games. In the preseason, I was scared. The ball beat me up pretty good. Like that Hall of Fame game in Ohio. That was bad, a mess.

You played in every game your first three seasons, but not as a starter until your fourth season when you also won the NFL Fastest Man Competition. Who did you beat to get it?

That was great. We thought it was going to be a Raiders-only race, but there were about 12 guys there from all the teams. The players picked were known for speed but it was one of those things where it was up to you if you wanted to participate. Me and Trapp [James Trapp, another track star] came from the Raiders. We ran a prelim then got down to the final three. I was fortunate to beat my teammate and win it.

In 1997, you ranked second among NFL receivers with a personal-best 12 touchdowns and a career-high 46 receptions for 804 yards. You’d reach another career high the following season. You must have been on top of the world.

It was all about timing, opportunity and having the right people in the right places. We had a good offense but no defense. We put record numbers on the board for offense. Quarterback Jeff George had a gun. He loved to throw that ball downtown. He used to tell me to ‘get ready cause it’s coming.’ The game that started it all was Atlanta. He gave me a signal and I caught it with one hand and ran it for a touchdown and that was the beginning of me leading the league in scoring.

The Raiders had some lean years but you played for the organization when they won some wild card and divisional playoffs, and in 2002, made it all the way to the Super Bowl, which was lost to Tampa Bay. What were the highlights?

My first year was probably one of the most memorable. I was a Bronco fan, so it was weird when we went to Mile High Stadium. My number got called and I ran the ball back for a 74-yard touchdown and it was wild. The first year we went to the playoffs was huge, too. Of course we played Denver again. We played them twice…the last game of the season and then the wild card game. I ended up scoring in the wild card game. But I was tired and washed out. It was my first year and the pro football schedule is rough. We ended up winning and going to Buffalo for the divisional playoff game. We got up there and it was cold. It’s not easy after living in California. All year, we’ve lived and died by the pass but we get there, and they can’t stop the run so we ran the ball. That strategy worked the first half, but I was wondering why were still doing it in the second. And we lost. We should have won that game.

You finished your career as the eighth-leading receiver in Oakland Raiders history, an impressive legacy. Did you leave the sport feeling satisfied?

Everybody wants to play and thinks they’re invincible. There is always someone coming in and trying to take your place that is younger, faster and stronger. I knew if I got so many years, I would be happy. The average NFL career is three-and-a-half years, and I got to play a lot longer than that. I can’t complain.

What football players and track stars meant the most to you during your career and do you keep in touch with any of them now?

When Jerry Rice came over from the 49ers, we were like boys, getting in trouble. We became good friends. I talk to him and Tim Brown. Harvey Williams, who was a running back, and I play golf together. A few years back, when Al died, his son had a big thing for him in Vegas. That’s where Al went every year on his birthday. His son brought in everyone who meant something to Al. It was great to get together with the guys. Once you finish playing, everyone moves on and you don’t really keep in touch so it was great to go back and bump into a lot of guys and just see them and touch elbows again. It makes you want to keep in touch. You never know when you’re going to hit the bottom of the barrel or get a condition.

How did you transition to a life after track and pro football?

It’s been rocky, like anything else. I’m married now with three kids. It’s been a big transition, as far as stopping working. Things change but you still have priorities. I was fortunate to play as long as I did, so I have some things lined up that a lot of guys don’t have. Or guys get banged up and can’t remember things.

One last thing — how fast do you think you could run the 100 now?

I was pretty good at getting up before, but once I stopped working, now I don’t want to get out of bed. I go down to the gym and try and stay halfway healthy, but run the 100? Maybe in 20. It won’t be no 10! I’d probably pull a hamstring.

JAMES JETT AT A GLANCE

Sport: Track and professional football

World championship titles: Olympic gold medalist in 1992 but also known for being the fastest man in West Virginia in any era, and as one of the six best NFL players who were Olympians

Personal bests: 10.10 seconds in the 100 meters, 19.91 seconds in the 200 meters; finished football career as the eighth-leading receiver in Oakland Raiders history

Nickname: On the Raiders, known as “Batman”

Years active (in any sport post high school): 14

Hometown: Charles Town

Current residence: Martinsburg

Age: 45

Family: Married to Amy. Three children: son James Jr., 18 and daughter Jordan, 18 (twins) and daughter Ava, 5